Lollapalooza: The Uncensored Story of Alternative Rock’s Wildest Festival is an upcoming oral history about the Lollapalooza festival, from its genesis as a farewell tour for Jane’s Addiction in 1991 to becoming a counterculture touchstone by the end of the decade. The book comes out March 25 on St. Martin’s Press. Written by veteran music journalists Richard Bienstock and Tom Beaujour, it includes interviews with more than 200 people, including the fest’s organizers, bands, stage crews, promoters and more.

Excerpted from LOLLAPALOOZA: The Uncensored Story of Alternative Rock’s Wildest Festival by Richard Bienstock and Tom Beaujour © 2025 by the authors and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.

Lollapalooza by Richard Bienstock & Tm Beaujour

St. Martin’s Press

TED GARDNER (manager, Jane’s Addiction; cofounder, Lollapalooza) The genesis of it all was that Perry decided that Jane’s Addiction was gonna break up.

GREG KOT (music critic, Chicago Tribune) It was well known that they were not loving each other as a band at that point.

STUART ROSS (tour director, Lollapalooza) I don’t believe that Perry felt that the trajectory of the band versus the extracurricular activities of the band were sustainable. And when Perry decided to break the band up, he was very specific that he wanted them to go out on a high note, rather than fade into obscurity.

NIKKI GARDNER (assistant to Ted Gardner; special groups coordinator, Lollapalooza) Lollapalooza would be their big farewell, with a bunch of bands getting together to celebrate the end of Jane’s Addiction.

STEVE KNOPPER (editor at large, Billboard magazine) It’s actually a canceled appearance at the 1990 Reading Festival that sparks the whole thing. Which is kind of funny to think about—that a show that doesn’t even happen leads to something so much bigger.

MARC GEIGER (agent; cofounder, Lollapalooza) Jane’s is playing the Reading Festival, and they have a warm-up club show. It’s a tiny club. Can’t remember the name of it. It was about 180 degrees inside. The walls were sweating. Simon Le Bon’s in the club. Everybody who’s somebody made it to that show for Jane’s Addiction. It was an amazing show.

CARLTON SANDERCOCK (owner, Easy Action Records; Jane’s Addiction superfan) It was a club called Subterania, underneath a flyover in West London. Jane’s Addiction, prior to that point, were cult in the UK, but by summer of 1990 they were a big band, and for our small group of people who were crazy about them, to see them in a club like Subterania was a f-cking big deal.

DAVE NAVARRO (guitarist, Jane’s Addiction) I totally remember that show at Subterania, and I’ll tell you why. I was a big heroin user back then, and the day before, I had hooked up with a bunch of street kids that knew where to cop. We got ahold of a bunch of dope and ended up going to a squatters’ flat in an abandoned building.

So me and a couple of these street kids were getting high, and somewhere along the line, I overdosed. And then all the kids that were living there, except my one friend, split, because they didn’t want to have a body on their hands. They all ran away, and my friend called an ambulance and dragged me down a flight of stairs to put me on the street corner to hopefully have an ambulance come and pick me up. And he said that when he pulled my body up to lean against a street sign, I started coughing. I had come back. So he had to pull me back up the flight of stairs and watch through the window as the paramedics were looking for whatever it is they were looking for. And they never found it and they went away.

I remember coming to the next day, somewhere in the afternoon. And my friend was perched over me, saying, “Dave! Dave! You were dead! You were dead last night!” I was completely confused. And the first thing I said to him was, “Is there any more dope left?” So my next move was to get high again, which is insane.

Then I realized that the Subterania show was that night. I looked at the clock, it was at four or five in the afternoon, and I think I had missed sound check. And this was before cell phones and computers. So I had to somehow find the venue, and I think I made my way there maybe twenty minutes before we were supposed to go on. Just before the show I was completely asleep, and someone had to tap me on the shoulder and say, “It’s time.” So I went from an immediate drug-induced sleep to being onstage. And then we played, the show went great, and everybody had a good time.

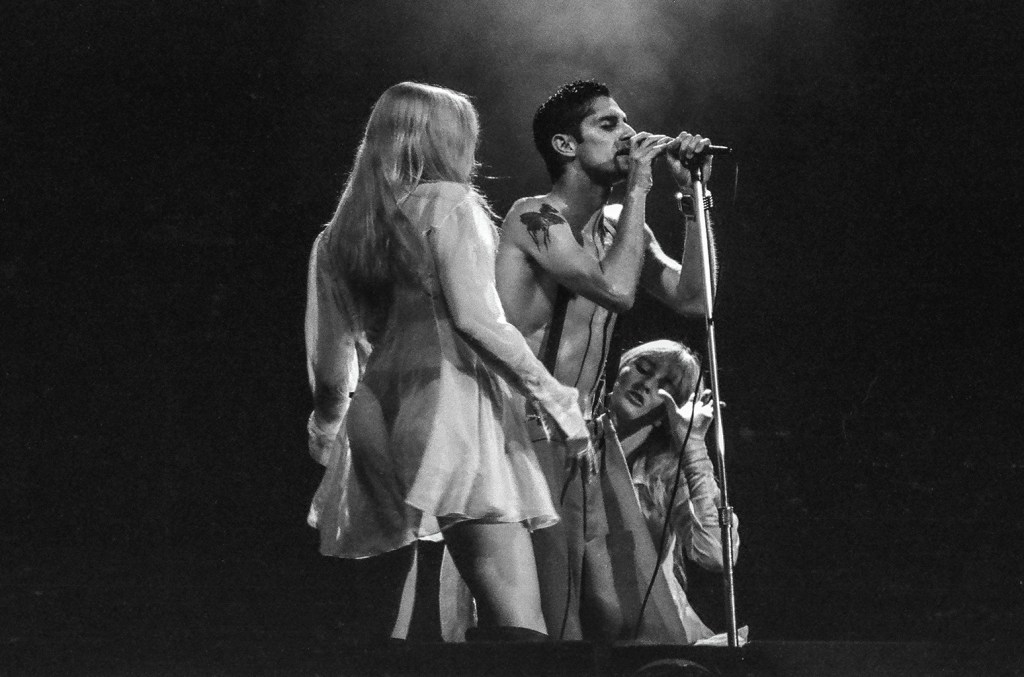

STEPHEN PERKINS (drummer, Jane’s Addiction) I tell you, man, nothing is better than playing to a roomful of people that want your music. They know the lyrics, they’re there for you. There’s a union. And Perry, he’s a shaman when he’s up there. You can go into the room and let him take you somewhere.

CARLTON SANDERCOCK I just remember the f-cking heat.

MARC GEIGER It was cool outside, hot in the club. Perry went outside after the show, caught a cold, lost his voice. Perry wakes up in the morning, the band cancels because he can’t sing.

PERRY FARRELL I got too f-cked up. So I didn’t make it to Reading. My voice was just shot.

DAVE NAVARRO I felt bad for Perry, of course, because no one wants to get injured like that. But I remember a sigh of relief coming over me that I could just go back to my hotel room instead of to Reading.

MARC GEIGER Stephen and I go, “F-ck it. We’re going down to the fes- tival anyway. We’re going to have a good time.” We went all three days. There’s a thousand bands: The Pixies, who were friends and my client, and were ruling the UK at the time. Inspiral Carpets were my client. The Fall was a client. And we had such a good time hanging with all of them. Stephen and I said, “This is what we should do in America.” A camara- derie of all these cool alternative bands.

STEPHEN PERKINS We knew the music was growing. We knew X and Black Flag and the Minutemen, all the bands that inspired us, they had hit the ceiling. But when we saw what was happening at Reading, there was the sense that there’s something about this music that’s not being shown or heard yet. And we knew the audience was there and ready for it. To have that eclectic day, eclectic night, that experience where the genres kind of just melt together and the fans are there.

MARC GEIGER They didn’t have this in America. So we went back to the hotel, and we described our day at Reading. With Jane’s, Perry had said, “We’re breaking up the band. We want to do something magical for our last tour.” So at that point, I described what I thought a format should be, and I said, “I think we should bring seven bands. Everybody should pick a band.” I literally just threw it out there, and everybody started picking bands. I was like a waiter taking orders, including my own. I think Dave picked Siouxsie and the Banshees, and Eric picked the Butthole Surfers . . .

ERIC AVERY (bassist, Jane’s Addiction) I was a huge Butthole Surfers fan.

MARC GEIGER . . . and Perry picked Ice-T, and I picked the Pixies and Nine Inch Nails, and Stephen picked Rollins, I want to say.

DON MULLER (agent; cofounder, Lollapalooza) They came back from the UK and said, “What do you think? Can we do this?”

MARC GEIGER When I went to contact the bands, everyone said yes. Except the Pixies.

JOEY SANTIAGO (guitarist, Pixies) That probably sounds like something stupid that we would do. I mean, we should have done it. Because we worked with one of the founders—he was our agent. So it’s like, “F-ck, why didn’t we do it?”

MARC GEIGER So then the Pixies choice eventually evolved into Living Colour. Great rock band. And they had the only hit record out of the whole bunch.

DAVE NAVARRO My first memory of hearing about the festival was in our rehearsal space. I wasn’t very coherent for the days prior, but that conversation didn’t happen until we were well back in Los Angeles. We were in this dingy little studio, and we kind of threw names around of who would be good to be on it. I just thought it was going to be another festival gig. I had no idea what it would become.

DON MULLER I’ll be brutally honest with you, we didn’t have a clue about what the hell we were doing. Zero. If anybody says differently, they’re lying. Because it was like, Okay, we’re going to put all these bands together, and we think we can move it around the country . . . but what do we do with it?

RICK KRIM (executive, MTV) This was 1990, 1991, way before festivals were really a thing over here. These days you have three festivals every weekend. There’s nothing unique about it. But at that time, and in this musical lane, no one had done it on that kind of scale.

GINA ARNOLD (journalist, author) Marc Geiger told me, “Oh, we have this great idea. We’re gonna do these festivals, just like in England . . .” And I was like, “That’s never gonna work.” I mean, think about the difference between those festivals and America. The size of America . . . it’s just too big. Also, I told him, “There’s no market for those bands.”

MARC GEIGER But the key point was it wasn’t about creating an alternative tour to represent the time. Jane’s was looking for ideas to go out with a bang, something different, okay? This is true. They’ll tell you they were splitting up. They were fighting, da, da, da, da, da. I think Eric was trying to be straight and the other guys were not. That was causing some frictions.

Now, it turned out that the right thing was reflecting alternative culture in a package that could get to a lot of people and be presented with force. But it wasn’t the front burner. Reading and England was the front burner. The back burner was the hair-band sleeve. MTV in England wasn’t showing Faster Pussycat and Winger videos every thirty seconds. England was Inspiral Carpets. Madchester. The BBC and Pete Tong and John Peel and Nick Cave. America was still scared of that. At Reading, the Pixies were headlining an eighty-five-thousand-person festival. Here, they were a club act. You’re trying to get that culture and that mindset over in America, which is still promoting Winger videos.

DAVE NAVARRO I wasn’t really aware of it being a farewell tour, just because we were on the verge of every show being a farewell show. I think that’s what Perry had in mind, but I don’t know that he shared that with us. Although it was pretty obvious to me that we weren’t going to be doing much after that.

PERRY FARRELL I told Marc, “I’m out of here after the tour, so let’s do something good.” And he looked at me and said, “Perry, you can do whatever the f-ck you want.” And I said, “I’m going to hold you to that.”

STUART ROSS Perry called us all in for a meeting and told us what was going to happen and what his concept was. I remember it as being Ted Gardner, Marc Geiger, Don Muller, and Peter Grosslight, who was one of the partners at Triad. Tom Atencio, one of Jane’s Addiction’s managers. Bill Vuylsteke, also known as Bill V., who was the business manager. I think it was at Bill’s office. And Perry sat us all down and said, “Guys, I’m breaking the band up. I want to go out on a high, good note. And for the last tour, we’ll get six other bands. We’ll get the promoters to provide crazy food like giant burritos, and we’ll do politics. We’ll get the NRA to set up a booth next to PETA. And we’ll get crazy art. And I’ve got a name for it, we’re going to call it Lollapalooza.”

PERRY FARRELL I do remember coming up with the name. Because everybody always wants you to title a tour. In all truth, it was a very humble moment. I was on a dirty carpet in an apartment in Venice. It was a shag carpet, I think it was green, it was kind of ugly, and there were crusty things on the carpet. I had books, like old secondhand books, and I picked up a dictionary. It’s kind of a rarity to have a real dictionary, but we all had them in those days. I used to like to use the dictionary for words when I would write songs, because you might run across a word that’s so amazing that it sparks something. And then sometimes I would read the dictionary just for fun. But I came across “lollapalooza,” because I was up to L.

TED GARDNER No one could pronounce it. No one could spell it.

STUART ROSS Nothing like this had been done before. There were a few festivals like WOMAD, which was the Peter Gabriel event that started in Europe that traveled a bit. And I believe there was one other smaller festival . . .

DON MULLER I don’t want to throw water on our fire, but there was a show down at the Pacific Amphitheatre in Costa Mesa called A Gathering of the Tribes, I think that was 1990. And that pretty much was a model, even though nobody wants to talk about it, of how to put something like this together. It was the vision of Ian Astbury from the Cult. I was a huge Cult fan, and I went and saw the show and I thought, F-ck, this is amazing. But then again, living in Southern California, it works, right? But not in Cleveland.

STUART ROSS But none of us ever said, “How are we gonna get these bands on and off the stage? We should reach out to the Gathering of the Tribes people.” I don’t think we even called those things traveling festivals at the time. They were kind of “multi-act packages.” None of them were considered operations where we could just use their playbook. This was a much larger scope.

MARC GEIGER This was a presentation of this music and culture in a format that could get to everybody. Because it wasn’t England. It wasn’t a small country. You already had some culture in pockets, right? You had KXLU and KCRW and 91X and KROQ in Southern California. So those people benefited compared to others. You had to take this around.

This is where Stuart Ross and the whole team need their credit. Those guys made it work. They were killers. They figured out how to mobilize an army. That’s a little different than setting up base camp, which is today’s festival model, right? “I’m going to build a big village, and we’re not going to move for three days, and then I’ll tear it down.” That’s a very different product, massively. There were tons of logistical challenges.

STUART ROSS We were creating something that literally had to be redone every day. None of us had experience in putting together a seven-act traveling concert package with a ton of extra activities going on. And so we leaned on the promoters. We said, “Okay, you’re going to book Jane’s Addiction, and you’re going to book six other opening acts, and here’s who the acts are, and here’s what you’re gonna pay them.” They weren’t offered separately, but they were contracted separately. The promoters were told who the bands were going to be and what their guarantees were going to be. But there was no, “Oh, I don’t wanna pay that much for this band.” That was not an option.

And then we said, “And we need you to find alternative food”—not just the hot dogs and hamburgers and pretzels that were kind of prevalent as venue food in those days—“and if you can invite any political groups that want a table, that would be great.” And we got, obviously, varying results.

T. C. CONROY (front-of-house coordinator, Lollapalooza 1991) It was my job to make that field turn into Perry’s dream. And he was ethereal about it because he’s an ethereal guy. He was probably really high, too. But what they did was they gave me an office at Triad: “Here’s your desk, here’s your telephone, here’s your legal pad, here’s your Yellow Pages.” And I would go into Triad every day and work on organizing that front of house. And it was not easy because nobody knew what Lollapalooza was. I mean, it was a cold call . . . the coldest of cold calls. Because if you think about it in context, even the word “Lollapalooza” was weird. “Lolla what? Can you spell that?”

MISSY WORTH (marketing consultant, Lollapalooza 1991) Perry was very insistent on making sure that we represented the alternative world, both onstage and off. For instance, I remember having a big discussion with him, and I’m just using examples, I’m not saying they were on the tour, but it was, “If you’re gonna have the ACLU, do you also have the NRA?” Like, “You have to represent the world, not just our point of view.”

PERRY FARRELL I wanted to have a debate booth where the Republican and the Democrat and the Independent each gets up there and says their thing. Because doesn’t that seem, like, fair?

T. C. CONROY He asked me to get pro-lifers and then get the abortion clinics, and to get the military and then get Greenpeace. He had this concept of, “It all goes on the field.” The liberal side was more open to the concept. On the other side, I just remember them all saying no.

GARY GRAFF (music writer, Detroit Free Press) In the US we didn’t have the culture of the midway with all the booths, whether it was merchants or social causes or whatever else. It was an unusual thing.

STUART ROSS When we talked to promoters and said that we needed art, they pretty much all passed on that. Because they couldn’t figure out how to do it. So Perry found an art gallery owner in West Hollywood. Didn’t really work out well, but he curated it for us.

DON MULLER Stuart and I did most of the work putting the actual deals together, and it was literally going out and talking to people and saying, “Hey, do you believe in this?” “Can we work this?” “Do you need backing?” Because a lot of the promoters just didn’t have the wherewithal or the resources to do a show of this magnitude. But we needed them on the ground. We needed them marketing. We needed to hit all the clubs. We needed to work radio. There needed to be cohesiveness in getting the message out. Also, the idea was to be able to play a GA [general admission] place, so the kids could come and go as they wished.

STUART ROSS We’re talking about 1990, going into 1991, and amphitheaters were the new cool thing. They’re not the shopping centers that they are now. And everybody wanted to play them. They were brand-new buildings and they held eighteen thousand people, and there was a big general admission component. So that’s where we wanted to play.

DON MULLER It was one of those situations where we were, in a weird way, creating promoters in different cities as we went along. Seth Hurwitz is one that comes to mind. He had the 9:30 Club in D.C., and he grew his business off alternative music and things like Lollapalooza. We go to Toronto and there’s a guy named Elliott Lefko who gets it, breathes it, understands it, and likes it. Great Woods in Boston, same thing. But then we had people like Belkin Productions in Cleveland, which, for all intents and purposes, didn’t know what this was at all. I’m not certain if I sold that show or Geiger did, but we sold the show.

STUART ROSS Danny Zelisko, who had Compton Terrace in Phoenix, an alternative venue, was one who got it. As did Andy Cirzan with Jam Productions, who had the World Music Theatre in Chicago and Harriet Island in St. Paul, another unusual venue.

DANNY ZELISKO (promoter, Evening Star Productions) Festivals at that time were kind of passé—Woodstock happened twenty years earlier, and it just wasn’t something that was going on. Lollapalooza was a brand-new thing that we had to explain to the market and to rock audiences everywhere.

ANDY CIRZAN (promoter, Jam Productions) I’d already been working with Don and Marc, because I had relationships with a number of their bands, like the Beastie Boys. When they started talking about this, all I was saying was, “I wanna be involved. Okay? Please let me be involved!” It wasn’t a question of, “What are you guys doing?”

STEPHEN PERKINS I think promoters and everyone realized that this music is bigger than we thought it was.

DON MULLER We were also smart about our ticket prices. We knew we needed to be realistic about what we were doing.

STUART ROSS Our tickets were $27.50 the first year. And these were the days before Ticketmaster charges cost more than the ticket, so there might be $2.75, $3.00 on top of it. That was it. In 1991, that was a moderate price.

DON MULLER Some of these promoter guys we had to browbeat, but we were going, regardless. If you wanted to be a part of it, great. If you didn’t, you didn’t. But we were gonna make this thing happen.

BOB GUCCIONE JR. (editor, publisher, SPIN magazine) Lollapalooza came along and was a natural organic invention. I look at so many of the music festivals today, and they’re such total sh-t because they’re trying to re-create a blueprint from other times. You know, there’s no point in replicating Woodstock. You can’t re-create that spontaneity or authenticity. But Lollapalooza was purely a product of the imagination of the people of its time.

GARY GRAFF It was Brave New World in a lot of different directions, because festival culture in the United States really didn’t exist in ’91.

PERRY FARRELL It was early years. Do you know that 1991, that was the year Michael Jordan won the NBA title? Also, the World Wide Web was formed that year. And for mystics—if you speak to the sages—the rebbe, his greatest writings came in 1991, when he was talking about Mashiach and the era of redemption, ushering it in. It was all in 1991. So I look at that period as all the strong things that happened at that time. And that made Lollapalooza possible.

Comentarios